Blog

Unpriced spill-over effects of close proximity data centres.

There are approximately 11,000 data centres world-wide, as of December 2025. This number is rapidly growing as many internet services are increasingly reliant on cloud-based digital support. Between 2019 and 2024 data centre capacity grew 2.2 times, while commitments to build data centre capacity grew 6.9 times over the same period (DC Byte, 2025). Data centres support a wide range of technologies: Artificial Intelligence (AI), blockchain and crypto currencies and other enterprise cloud computer applications.

The allocation of scarce resources to support data centre operation contributes to rising electricity and water prices. In the immediate post-Covid-19 inflation period, additional cost pressures for many households in Europe and the United States are most unwelcomed and is a threat to their economic well-being. The common association between undeveloped land and reliable supplies of water and electricity for residential areas and data centres creates local government pressures.

From an economic perspective, the rapid growth in data centre construction presents several issues. These include:

- cost pressures that threaten economic well-being for local residential communities (i.e. meeting basic needs);

- unpriced negative health spill-over effects due to the proximity of data centres to residential neighbourhoods; and

- supply-side AI-robots-cloud computer drivers of economic growth.

This blog summarises the first two points listed above. The third point is summarised in a separate blog (Abieconomics, 2025).

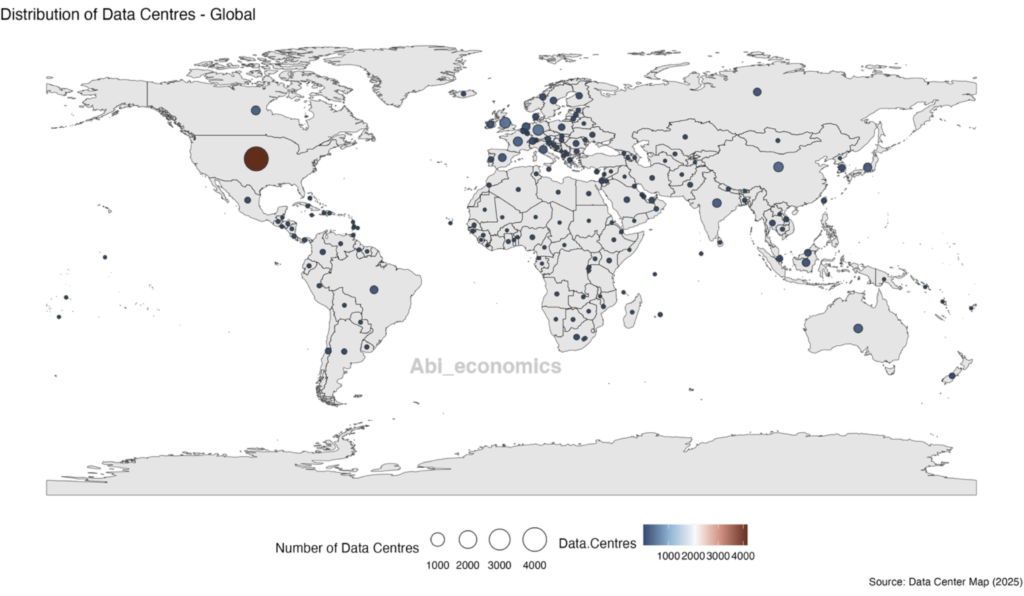

The distribution of data centres is scattered across the globe. However, the Unites States has a particular concentration with 4264 centres (as of 07.12.2025), followed by China (500-600 estimated), United Kingdom (499) and Germany (487) (Data Center Map, 2025). The concentration of data centres in the US is in line with the large investment by US-based firms: Google, Amazon, Microsoft and OpenAI (see Abieconomics blog post). Figure 1 demonstrates the global distribution of data centres, with particular concentrations in the United States and Europe.

Figure 1: Distribution of data centres globally.

The United States has 38 percent of the world’s data centres (Data Centre Map, 2025). The strong investment in digital infrastructure (exemplified by data centres) is driven by market and geopolitical competition between the US and China.

“However, the ownership of cloud computing infrastructures is heavily polarised. US-based Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud control roughly 70% of the market for on-demand cloud computing infrastructure services globally, while Chinese tech giants Alibaba, Huawei, and Tencent control much of the remaining 30%. These leading cloud providers are called ‘hyperscalers’, in part because their infrastructures allow other organisations to rapidly ‘scale up’ their computation and data storage use on demand” (Lehdonvirta et al., 2025).

Demand for data centre services is expected to increase the pressure on water and electricity services. The reliable and affordable supply of these essential services is already suffering from cost-push inflation. Demand increases are likely to exacerbate supply pressures. Demand for data centre services in the United States is projected to increase between 18 to 27 percent by 2030 (McKinsey and Co, 2025). Over the same period data centre electricity consumption is expected to increase over 300% by 2030 (assuming a 22% increase in demand), from 2023 levels (McKinsey and Co, 2025). The affordability pressures of accessing these essential services in local communities is a local political concern in regions of the US (Chen, 2025).

The projected energy demand of data centres in the United States is underscored by the plans for privately owned nuclear power plants and unprecedented private investments of hundreds of billions of dollars.

“Meta and Microsoft are working to fire up new nuclear power plants. OpenAI and President Donald Trump announced the Stargate initiative, which aims to spend $500 billion—more than the Apollo space program—to build as many as 10 data centers (each of which could require five gigawatts, more than the total power demand from the state of New Hampshire). Apple announced plans to spend $500 billion on manufacturing and data centers in the US over the next four years. Google expects to spend $75 billion on AI infrastructure alone in 2025” (O’Donnell and Crownhart, 2025).

Figure 2: Scale of data centres in North America and Europe (29.11.2025).

On the outskirts of Washington D.C, the state of Virginia is home to 667 data centres, 16 percent of the total in the US. In particular, in the county of Loudoun the communities of Ashburn and Stirling support 152 and 111 data centres, respectively. Loudoun county, known as ‘data centre alley’, has a mix of residential and light industrial land that pushes into traditional agricultural regions of the state. The increased density and scale of the data centres produces negative health and cost-of-living pressures for pre-existing, neighbouring households. Some households immediately next to large data centres experience sleeplessness due to high levels of background noise. However, a legislative review of Virginia’s data centres in 2024 stated that: “[a]lthough noise has been a problem for some data centers, a large majority of data centers do not generate noise complaints because of their location or design” (JLARC, 2024). The price of electricity in US areas near data centres has gone up 267% according to Bloomberg News research (Faguy, 2025).

Carbon emissions of electricity used by data centres are another source of unpriced costs. According to the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), “Nationwide, data centers could contribute to 600,000 additional asthma-related symptom cases and over $20 billion in public health costs by 2030, according to researchers at the University of California, Riverside and Caltech” (Henjes, 2025). The unpriced nature of such emissions are exacerbated by the lack of a national US carbon tax or tradeable permit scheme.The expected negative health effects of close proximity large data centres are not currently priced by data centre operators. While these data centre operators may care about the real or perceived negative impact of data centres, the US market for data centres does not include such social costs in their total and marginal cost calculations. As a result, a negative externality of production is caused. Figure 3 presents a model depicting the distinction between the social and private costs of supplying data centres in close proximity to households.

Figure 3: Non-price spill-over effects of data centres in close proximity to residential neighbourhoods.

The separation between marginal social and private costs represents the monetary value of the non-priced spill-over effects of the negative health effects (through noise pollution) of incessant operation of cooling systems. The shift of the supply curve (S => S1) maps the potential scenario of more data centres being built in close proximity to households. In this scenario negative externalities grow larger.

In order to reduce or eliminate the negative externality of production, some form of government intervention is likely required. In the case of data centres and their proximity to residential neighbourhoods, possible interventions include:

- direct compensation from data centre owners to affected households;

- indirect tax (Pigouvian); and

- regulations that limit the proximity of data centres to residential land.

Each of these interventions would cause the S1 curve to shift leftward towards MSC curve. Thus, reducing the quantity of close proximity data centres and achieving a quantity at or closer to QOPT.

The market and non-market effects of intense operation of data centres is an example of the time lag between ‘new’ production processes and adequate government oversight. The relatively unique operation of data centres and the rapid growth in their number in select locations illustrates the short-comings of local land-use planning processes. In addition, intensive use of scarce resource (electricity and water) by data centres compounds pre-existing economic negative externalities of pollution (fossil fuel-based electricity production) and economic well-being of households. The close proximity of large data centres to residential areas (as highlighted in Virginia’s ‘data centre alley’) gives rise to a unique negative externality of production that is low-volume, but constant, noise pollution. Government intervention is required to balance the competing demands for land-use.

References

Abieconomics (2025). Say’s Law, Artificial Intelligence, and Technological Change. Dr Ricky Ray blog, 20.08.2025. https://abieconomics.com/says-law-artificial-intelligence-and-technological-change/ (Accessed: 09.12.2025).

Chen (2025). ‘The new price of eggs’. The political pressures of data centers and electric bills. New York Times, 30.11.2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/11/30/us/politics/data-centers-electric-bills-georgia.html(Accessed: 03.12.2025).

Data Center Map (2025). Data Centers. www.datacentermap.com/datacenters/ (Accessed: 3.12.2025).

DC Byte. (2025). 2025 Global Data Center Index. https://www.dcbyte.com/global-data-centre-index/2025-global-data-centre-index/ (Accessed: 07.12.2025).

Faguy, A. (2025). A humming annoyance or a job boom? Life next to 199 data centres. BBC News. 26.10.2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c93dnnxewdvo (Accessed: 05.12.2025).

Henjes, K. (2025). The growing demand for data centers in the US. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 21.08.2025. https://www.aaas.org/news/growing-demand-data-centers-us(Accessed: 08.12.2025).

JLARC (2024). Data Centers in Virginia. Commonwealth of Virginia. https://jlarc.virginia.gov/pdfs/reports/Rpt598.pdf (Accessed: 08.12.2025).

Lehdonvirta, V., Wu, B., & Hawkins, Z. (2025). Weaponised interdependence in a bipolar world: how economic forces and security interests shape the global reach of US and Chinese cloud data centres. Review of International Political Economy, 1-26.

McKinsey and Company (2025). Scaling bigger, faster and cheaper data centers with smarter designs. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/private-capital/our-insights/scaling-bigger-faster-cheaper-data-centers-with-smarter-designs (Accessed: 01.12.2025).

O’Donnell, J. & Crownhart, C. (2025). We did the math on AI’s energy footprint. Here is the story you haven’t heard. MIT Technology Review. Power Hungry: AI and our energy future.

https://www.technologyreview.com/2025/05/20/1116327/ai-energy-usage-climate-footprint-big-tech/ (Accessed: 07.12.2025)

S&P Global – Data centres driver of GDP growth in US