Blog

Income inequality, global trade, and U.S. tariffs.

Undoubtedly, the United States President Donald Trump’s second term in Office has dramatically changed the global trade landscape. President Trump’s first term in Office shocked the United States to openly question the fundamentals of the global trade system. President Trump applied quotas during his first term (2017-2020). The following Biden administration (2021-2024) openly questioned the role of the World Trade Organization and introduced a range of production subsidies in strategic domestic technological industries. However, in President Trump’s second term in Office, he has more openly applied his neo-mercantilist1 trade agenda. An agenda that values: a) revenue and b) trade surpluses.

Global trade during the twenty-first century is blamed for rising income inequality in the U.S. Much has been written about the effects of the loss of manufacturing jobs in many rural areas of the U.S. and the associated rural economic decline. Economists’ Anne Case and Angus Deaton’s book Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism (2020) summarized the sharp rise in deaths by drug, alcohol, and suicide in economically depressed regions. The authors link this U.S. health crisis with rural economic well-being. Many in the U.S. believe that global trade is unfairly weighted against their domestic interests and that the U.S. government should intervene. New York Times reporter, Patricia Cohen writes of a U.S. study finding that many citizens want the U.S. government to do more to protect the economy: “Foreign trade is particularly prone to charges of unfairness,” Dani Rodrik writes, because countries operate under differing rules and conditions. Government subsidies, weaker health and environmental regulations or sweatshop conditions, for instance, bestow an unfair competitive advantage”. The targeting of global trade, by some in the U.S., as the cause of the decline in economic well-being for many with relatively low education levels, overly simplifies the wider set of economic changes occurring.

The rise of ‘superstar’ firms in the U.S. during the twenty-first century is associated with increased market share and historically low levels of wage returns to workers (as a ratio to profits). Economist David Autor and co-authors (2020) find that the expansion of markets through global trade and technological change has seen some firms raise their market share, increase their mark-ups (i.e., abnormal profits), and lowered the return to workers of the value added through the production process. Autor and co-authors (2020) do not support the argument that labor markets or minimum wages are the cause of the low return to workers in these ‘superstar’ firms. Such firms include: Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, and Uber.

The introduction of trade tariffs will not adversely impact firms such as Google, Facebook, and Amazon. However, tariffs may support a lower tier of U.S. firms. It is unlikely that the introduction of tariffs, alone, will improve U.S. income inequality. Assuming that minimum wages don’t change in real terms in the short to medium term, the increase in export revenue to firms, plus a possible increase in the marginal propensity to consume, will see firms increase their revenue and profit distributions to shareholders. Neither of these changes are expected to improve the relative economic well-being of the poor in the United States.

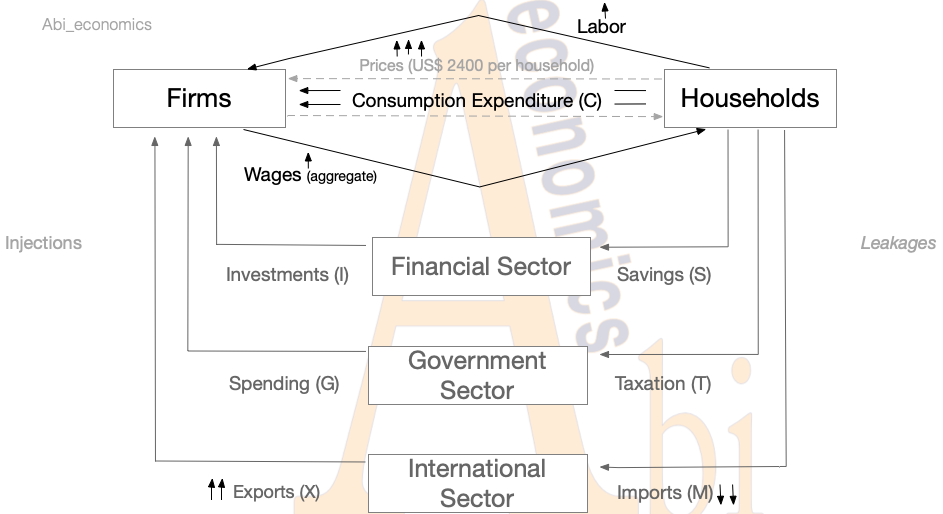

The Circular Flow of Income model (Unit 1, Chapter 1) assists in evaluating the expected impact of U.S. import tariffs on income inequality. The introduction of tariffs will increase the price of goods and services consumed in the U.S. The Yale Budget Lab estimates that prices will rise by US$ 2,400 per U.S. household (based on 1 August tariff levels). Without off-setting wage increases, one may assume that expenditure on goods and services will fall by the same amount. With 128 million U.S. households in 2024, this fall in expenditure would equate to US$ 307 billion per year. Figure 1 presents the effects using the Circular Flow of Income model.

Figure 1: Circular Flow of Income model (5 sector).

A partial offset of the fall in consumer expenditure is an expected increase in employment. Robert Z. Lawrenceestimates that manufacturing employment could rise by 1.3 million workers, or 0.9 percent of the US workforce. That equates to an increase of US$ 78 billion in aggregate household income, per year.

The net effect may be expected to be $307 – $78 = $229 billion. If one assumes that the US marginal propensity to consume (mpc) to be 0.5 annually2, and a Keynesian multiplier of 2 (Unit 3, Chapter 17), the impact of the fall in US household spending increases to approximately US$ 450 billion. This would be a clear reduction in economic well-being of many U.S. households.

The asymmetrical nature of the bilateral trade agreements that President Trump is negotiating with trade partners frequently results in zero export tariffs on U.S. exports. This will benefit business owners in the U.S. who export. Trade opportunities for U.S. firms will expand into new markets as trade partners agree to open previously closed sectors of their economies. In addition to the job growth identified above, expanding trade for U.S. firms will benefit business owners. They are expected to increase their revenues. The profits received by entrepreneurs will increase.

President Trump’s restructuring of global trade by reasserting U.S. terms of trade is not expected to improve income inequality. If anything, income inequality is expected to increase as a result of the current trade policy of U.S. President Trump. Wage earners, on average, are expected to experience a lower standard of economic welling. While export entrepreneurs are expected to increase their profits.

- Mercantilism was a popular view of trade in Europe during the seventeenth century. The generation of trade surpluses, and as a result, revenue was aim of leading European nations. This view of trade prompted the creation of the British East India Company and the Dutch East Indies Company, and the colonial practice of mass resource extraction.

- Auclert, A., Bardóczy, B., & Rognlie, M. (2023). MPCs, MPEs, and multipliers: A trilemma for New Keynesian models. Review of Economics and Statistics, 105(3), 700-712.

References

Autor, D., Dorn, D., Katz, L. F., Patterson, C., & Van Reenen, J. (2020). The fall of the labor share and the rise of superstar firms. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(2), 645-709. https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/publications/Autor%20et%20al_2020_The%20Fall%20of%20the%20Labor%20Share%20and%20t.pdf

Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2020). Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. In Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. Princeton University Press.

Cohen, P. (2025). Trade Fueled Inequality: Can Trump’s Tariffs Reduce It. New York Times (02.08.2025) https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/02/business/economy/trump-tariffs-income-inequality.html

Lawrence, R. L. (2025). Closing the trade deficit would barely raise the share of US manufacturing employment. Peterson Institute for International Economics (13.06.2025) https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2025/closing-trade-deficit-would-barely-raise-share-us-manufacturing

Rodrik, D. (2025). Shared Prosperity in a Fractured World: A New Economics for the Middle Class, the Global Poor, and Our Climate. Princeton University Press.

Yale Budget Lab (2025). State of U.S. Tariffs: 1 August 2025 https://budgetlab.yale.edu/research/state-us-tariffs-august-1-2025

By Dr Ricky Ray (08.08.2025)