Blog

Helping the poor: subsidies or cash transfers.

The policy question of how best to assist the poor is complicated and divisive. Government subsidies are a traditional market-based form of government intervention used. Alternative strategies include: direct government provision of free services and cash transfers. In learning economics, one is quickly taught that government subsidies introduce inefficiencies. Why does economic theory indicate that a government subsidy payment for poor households is an inefficient resource allocation? This claim of inefficient resource use is counter-intuitive. Many students initially think that assisting poor households to meet basic needs via a subsidy (i.e. making the product cheaper for households) is a ‘positive’ and therefore should not be associated with a negative phrase – like ‘inefficient’.

Perhaps equally counter-intuitive, is the preference of many economists to assist poor households with unconditional cash transfers (UCT). A BBC news article recent highlighted a trend in India of using UCT to pay adult women who work at-home a modest monthly amount (Biswas, 2025). UCTs can take several forms depending on a target audience: universal basic income for a general population or more targeted income-tested poverty alleviation transfer. Irrespective of the target audience, understanding why economists often prefer unconditional cash transfers is important to understand.

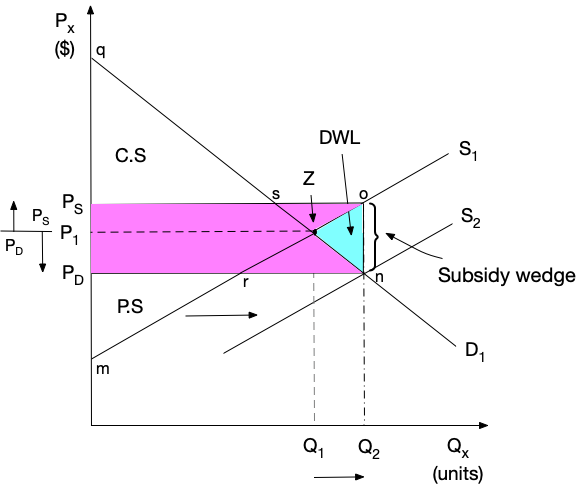

The subsidy wedge diagram (Figure 1) depicts both a welfare gains and efficiency losses due to the introduction of a subsidy. Part of the additional quantity produced and consumed (Q2 – Q1) is included in the Deadweight Loss (DWL) triangle (area Zon). When translating the subsidy model to a real-world product and context (i.e. subsidy for a small 3kg LPG gas bottle in Indonesia) the explanation for the DWL is technical. But how can giving to the poor be deemed inefficient and therefore include negative aspects?

Figure 1: Inefficiency associated with a government subsidy.

The answer lies in i) the preferences of consumers for quantities above Q1 and ii) producers’ marginal cost (MC) > marginal revenue (MR) for quantities above Q1.

Altering the market price, through a subsidy, in an assumed perfectly competitive market distorts the value of production and consumption above the equilibrium quantity. Some consumers are effectively forced to receive subsidy benefits for a good, which they don’t value as highly as the value of the subsidy. In a practical sense, some recipients of the subsidised goods (e.g. 3kg gas bottle) would prefer to direct the same money to another pressing use. Therefore, the costs of additional gas bottles sold (because of the subsidy) are valued by some consumers less than the value of the subsidy. The opportunity cost (i.e. the next best alternative foregone) is relatively high for these consumers. For quantities produced above Q1, MR is less than the MC of production. Therefore, resources are being allocated that are insufficient to motivate production.

Cash transfers may be used instead of subsidies to enable poor households better meet basic needs. The advantage of using cash transfers is that households may make autonomous choices and direct money to best meet their specific circumstances. However, some policy makers fear that money will be spent on non-productive consumption. As a result, conditional cash transfers are often preferred to unconditional transfers and extensive use of subsidies.

Several countries use conditional cash transfers as incentives to promote education and/or health investments among the poor. Cahyadi and authors express the use of conditional cash transfer programs in this way:

“Perhaps the most remarkable innovation in welfare programs in developing countries over the past few decades has been the invention and spread of conditional cash transfer programs (CCTs). These programs provide regular cash transfers to poor households to help reduce poverty but condition the transfers on households making a series of human capital investments in their young children. These conditions typically begin before birth— prenatal care and deliveries by trained midwives or doctors are usually conditions—and continue through early childhood health investments (for example, immunizations and growth monitoring) and enrollment in primary and junior secondary school (Cahyadi et al., 2020).

The focus of conditions on safe child birth and school enrolment for basic levels of education are widely viewed to provide private and social benefits (i.e. merit good). The use of such conditions are widely supported.

The inclusion of the conditionality of the cash payments may be justified based on several reasons (Attanasio et al., 2015):

- Existence of positive externalities of some actions;

- A more flexible form of a traditional government subsidy payment; and

- Overcome reluctance of parents to otherwise invest in health/education services.

Cash transfers to poor households, without conditions, is counter-intuitive for many. An over-riding concern is that cash given and not earned will be wasted or spent on unproductive goods and services with no controlling effects of conditions. So, the policy of providing stay at-home Indian women with unconditional cash transfers in India may be a surprising policy.

In 12 out of 28 Indian states, approximately 118 million adult women receive regular cash payments from state governments. The transfers vary between US$12 and US$30 per month are paid directly to the womens’ bank accounts. The unconditional nature of the payments means that women are free to choose how they spend their money; one of the limitations of government subsidies.

Analysis of unconditional cash transfer (UCT) programs indicates that “strong and positive average treatment effects” occur, at the aggregate level, across nutritional, human capital and psychological well-being measures. The analysis by Crosta et al. (2024) includes 72 UCT programs, in 34 countries, that on average lasted for between 1-2 years. The data used in the analysis came from programs that evaluated treatment effects (giving UCT) relative to control groups. The phrase ‘Randomised Control Trials’ is used to describe such study designs that can generate causal statistical effects. The statistical analysis by Crosta et al. (2024) controlled for country income differences and whether the programs were conducted in rural or urban settings. Importantly, the analysis excludes UCT data when the program was “delivered in conjunction with other costly and non-trivial interventions, such as training, savings group formation, coaching, etc” (Crosta et al., 2024).

The use of India’s growing UCT for at-home women has a different focus than the exclusive poverty reduction focus of programs included in the Crosta et al. (2024) study. In India, the “[e]ligibility filters vary – age thresholds, income caps and exclusions for families with government employees, taxpayers or owners of cars or large plots of land” (Biswas, 2025). As a result, the private and social benefits will differ too.

The use of UCT and the associated resources to empower a segment of society bring into question the role of government. Governments have the authority and means to shape many aspects of an economy (DP economic 9 key concepts can be summarised through ‘ROO’: 2nd ‘O’ referring to Organization and the concepts of Choice, Intervention, Change and Interdependence: see Abieconomics, 2025a). However, the extent to which and in what areas a government should intervene is a philosophical question. One that largely lies outside the scope of economics. The budgetary and opportunity cost of India’s UCT scheme should also be considered.

Biswas (2025) states that the collective cost of the UCT for at-home Indian women is set to cost approximately US$ 18 billion in the current fiscal year. Many of the 12 states already face significant structural fiscal imbalances, where government revenue is systematically < then government spending. The sustainability of financing UCT is an important question. As the UK and France are experiencing in 2024-25, perceptions of unsustainable national debt can add to the cost of financing future debt (see Dr Ricky Ray blog: Abi economics,2025b).

The empirical evidence supports economic theory’s prediction that cash transfers are more effective (aka efficient) in supporting poverty alleviation. Conditional and unconditional cash transfers promote choice, utility maximization and don’t distort producer and consumer market valuations. When and for whom cash transfers should be used is a broader question that is in -part philosophical, part economic and part political.

References

Abieconomics. (2025a). IB economics – Units 1 – 4. www.abieconomics.com (Accessed: 12.12.2025)

Abieconomics. (2025b). The UK debt pressures. Dr Ricky Ray blog (29.10.2025). https://abieconomics.com/the-uk-debt-pressures/ (Accessed: 14.12.2025).

Attanasio, O. P., Oppedisano, V., & Vera-Hernández, M. (2015). Should cash transfers be conditional? Conditionality, preventive care, and health outcomes. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(2), 35-52.

Biswas, S. (2025). A wage for housework? India’s sweeping experiment in paying women. BBC, 09.12.2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c5y9ez3kzrdo (Accessed: 10.12.2025).

Cahyadi, N., Hanna, R., Olken, B. A., Prima, R. A., Satriawan, E., & Syamsulhakim, E. (2020). Cumulative impacts of conditional cash transfer programs: Experimental evidence from Indonesia. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 12(4), 88-110.

Crosta, T., Karlan, D., Ong, F., Rüschenpöhler, J. and Udry, C.R. (2024). Unconditional Cash Transfers: A Bayesian Meta-Analysis of Randomized Evaluations in Low and Middle Income Countries. NBER Working Paper 32779 (2024), https://doi.org/10.3386/w32779. (Accessed: 10.12.2025)