Blog

The UK debt pressures

What constitutes a sustainable level of public debt remains a topic of debt in economics? In 2025, the United Kingdom and France are experiencing acute fiscal pressures. Germany recently relaxed tight constitutional limits of public debt levels. The debt ceiling in the United States is seemingly annually increased, across recent years (Austin, 2025). After the successive crises of the Global Financial Crisis (2007-08) and the Covid-19 global pandemic (2020) national debts are at historical peace-time levels. After a prolonged period of low levels of interest from 2009 through to 2021, the full cost of public debt is being experienced, financially and politically: there have been five (5) French Prime Ministers over the past 2-years. France’s fiscal and debt problems are central to the current political instability in France. Even though, interest rates continue to be below the long-run average – see Figure 1. Although high public debt is not catastrophic, it is showing itself to be high destabilizing.

Figure 1: UK official interest rate, 1975 – 2025.

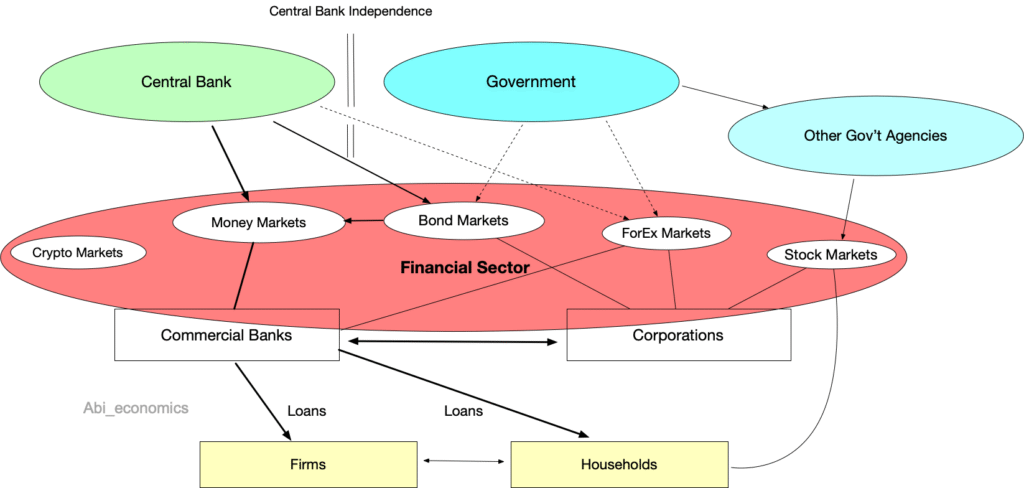

Monetary policy is built on the supply and demand for money. Money is primarily a medium of exchange, but indirectly is also a store of value. The money market is influenced by the supply of money via bond markets and demand for money is directly influenced by the official interest rates. The United Kingdom and France are currently experiencing severe macroeconomic pressures as the cost of issuing new debt (via the bond market) has increased, which is limiting central bank’s options to stimulate economic activity via interest rates. The three-way relationship between central banks, bond markets and money markets is depicted in Figure 2. The acute pressures being faced by the United Kingdom and France is challenging how economists conceptually understand the macro-economy.

Figure 2: Financial sector.

The theory of portfolio balance was the dominant perspective that underpinned the motivation of why economic agents bought government bonds and held money. Only two broad classifications of financial assets exist, according to portfolio balance theory, money and all other assets (i.e. bonds). The relative share of these asset-categories held determined monetary policy, that is the supply and demand of money. “Until the mid-1980s, the prevailing orthodoxy among economists followed Keynes, Tobin and Friedman in viewing portfolio balance effects as key to understanding how monetary policy worked” (Chadha et al., 2025, p.1864).

The new Keynesian model became the model of choice used by many economists to understand monetary policy and its effects on government debt. According to this view, monetary policy (and underlying Aggregate Demand) is determined by current and future short-term interest rates. Chadha et al (2025) state: “…in the standard New Keynesian model, all that matters for demand determination of aggregate demand is the path of current and future short-term interest rates; changes in the relative supplies of financial instruments, including money and government debt, have no role in shaping the yield curve” (p.1864). A bond’s yield represents the opportunity cost of investing money in government bonds.

The assumed application of the new Keynesian model is being challenged by empirical realities. The importance of market sentiments and their perceptions of risks, associated with the opportunity cost of buying government bonds in secondary markets, is having an effect in bond markets in the United Kingdom and France. In understanding the economic pressures being experienced by these two countries (and the associated political ramifications) a reevaluation of the utility of the new Keynesian model is warranted.

Government debt in isolation, ceteris paribus, is not a problem. Government debt is sustainable if repayments can be made and financial markets believe they can be made. Government debt is problematic when:

- financial markets incorporate perceived increased risk of non-payment or increased investment opportunity costs into the ‘price’ of buying bonds,

- buyers of government bonds are unwilling to lend money to governments, and

- structure of the national economy is out-of-balance and debt is required to pay for recurring expenditure.

Figure 3 plots the debt levels of high and emerging-income countries, along with the United Kingdom from 1974 to 2024. From the 1980s the United Kingdom had relatively low levels of debt. This changed towards the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century. Since the end of the Covid-19 global pandemic, while other high-income countries have lowered their debt levels, the United Kingdom has not.

Figure 3: National debt as a percentage of GDP for high-income, emerging-income and the United Kingdom, 1974 to 2024.

Figure 4: National debt repayment as a percentage of GDP for high-income, United Kingdom and France from 1974 to 2024.

Issuing of governments bonds is a primary method of raising money via debt. Bonds are an IOU for a fixed period – often for 1, 3 or 5 years. Buyers of the bond are paid an agreed interest rate each year, then are repaid at the end of the loan period.

Changes to the supply and demand for government bonds (in the bond market) directly affect the price of these bonds in the primary market. The primary market relates to the first sale of bonds. These bonds may then be on-sold in the secondary market. Changes in the price of bonds occurs in secondary markets. As aggregate bond prices fall, their yields increase. If the initial price was $100, but investors in the secondary market are cautious about buying government bonds, the price in the secondary market may fall to $95. This will result in an increase in the bond’s yield [(100 / 95)-1] = 1.053. The bonds’ yields represent the opportunity cost of investing money in government bonds. The yield also reflects the cost of governments to raise revenue by issuing bonds.

Yield curves for the United Kingdom (see Figure 5) indicate that markets are pricing for increased risk for UK bonds across the medium term. This will continue to place pressure of the UK with respect to financing existing public debt and raising new debt across the short-run. The inflation-adjusted yield curve in Figure 5 indicates that a UK recession may occur. The negatively sloped inflation-adjusted yield curve over 10-years (highlighted in red) provides some indication of market’s perceptions of the UK economy.

Figure 5: Bank of England yield curve.

Public debt pressure for the UK is not likely to decline over the short-medium term. Although current UK public debt continues to be manageable and sustainable, it is so, at a relatively high cost – an increasing repayment burden. This ‘cost’ will increase should the UK economy enter a recession and the current progressive government wishes to engage in expansionary fiscal policy. The cumulative debt burden would then be considerable. Financial markets would be expected to increase yields further, increasing the cost of raising public debt through government bonds. The importance of opportunity cost in helping determine the price of holding government bonds is again important. The prolonged period of low priced government debt is past and along with it, the New Keynesian model of monetary policy.

By Dr Ricky Ray (29.10.2025)